| STATEMENT | PROGRAM | KEYNOTE | PRESENTATIONS | PHOTOS | VIDEOS | LINKS |

|

||

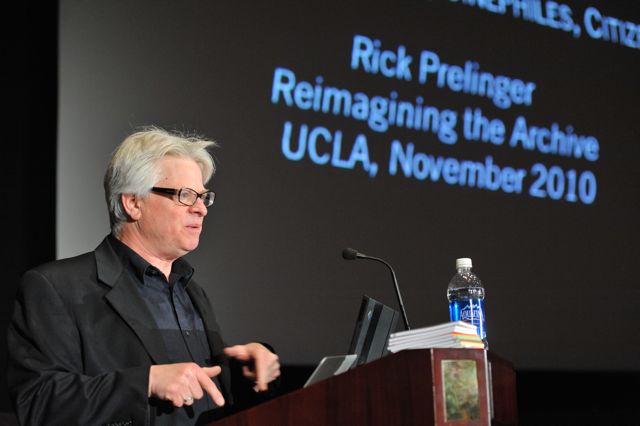

| KEYNOTE SPEAKER: RICK PRELINGER | ||

|

||

View more documents from Rick Prelinger. |

||

|

Rick Prelinger, an archivist, writer and filmmaker, founded Prelinger Archives, whose collection of 60,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002 after 20 years' operation. Rick has partnered with the Internet Archive to make 2,100 films from Prelinger Archives available online for free viewing, downloading and reuse. |

||

| RICK'S PRE-SYMPOSIUM BLOG POSTINGS | ||

"Archives: big or small?" - Rick Prelinger(posted 10/19/2010) No, I'm not musing about the optimum size of collections, nor am I pitting 35mm theatrical projection against cellphone video. Instead, let's try a thought experiment. If we can pretend for a moment that the emotional and cerebral intensity of a movie is equal to life, is archival footage (in all its authenticity, wonder and surprise) bigger than life, or is it smaller? You might never have worried about this question, but I've thought about it a lot while making my movie Panorama Ephemera, while compiling the annual Lost Landscapes of San Francisco shows, and especially while looking at raw archival material for my current film-in-progress. So, for just a moment, let's draw a line between archivists and viewers. Since I identify as an archivist, archival footage isn't just one of a number of elements in a story, it IS the story. When archival footage comes on screen, that's usually when the show starts for me. During documentaries, I find myself nodding out during talking heads and sitting up for archival material. Of course, I'm not an average viewer. Let me try saying this another way. Why does historical footage often seem to retreat into the background while contemporary imagery moves into the foreground? Why do historical images tend to appear smaller than life, while contemporary images often seem larger than life, hyperreal, more revved up? Archival footage feels immersive to us archivists because we love it and have trained ourselves to meet it more than halfway. But to other kinds of viewers, I suspect that the archival sequences might not be the strongest moments of most films. Why does archival equal cool and cerebral while contemporary equals warm and immersive? And why would members of an audience already motivated to watch a historically-focused piece find actual historical footage less interesting than, let's say, a reenactment or dramatization? As I said, I've thought about this basketful of questions while looking at work I've made projected on a big screen. And I started thinking about them again recently, while attending a lecture on 20th-century music by Alex Ross and Ethan Iverson. Specifically, I started to wonder why archival footage never gets to pull its own weight. It isn't dramatic enough. Or at least that's what producers, and perhaps viewers, seem to think. Silent footage is almost always "enhanced" by sound effects. Music, often emotionally and intellectually invasive, overwhelms the images. We rarely see more than a few seconds of archival material without some kind of sweetening or recontextualization, the proverbial "spoonful of sugar to help the medicine go down." Why aren't the images enough all by themselves? Is archival footage like a plate of unseasoned steamed zucchini? I think the problem might actually be this: We are moving into an era in which archival footage of actual events may be more highly valued as reference material than as actual elements of a film. Now, don't get me wrong. I'm sure we'll still see tons of archival footage on the screen and on the air. But in the same way that real footage of actual historical events might be becoming a poor relation of historical simulations, I think we're going to see more and more instances where historical images will simply function as templates for higher-production-value, dramatic and immersive dramatizations. Why use "old archival clips" in documentaries when you can build more immersive sequences on the desktop? Not that I don't applaud the potential use of archival materials in the construction of simulations and artificial worlds. Such use, if inventive, could combine past and future in fascinating ways while generating lucrative stock footage business for financially pressed archives. But I wonder whether marginalizing original documents in favor of hyperreal recreations will drive another nail into the archival coffin. If we are to avoid the devaluation of the historical document, we must try our best to defend the power of the original image. As archivist Pam Wintle once told me, "every frame is precious," and while our senses of cultural and historical value may vary over time, we have only one chance to document an event and infinite opportunities to reconstruct it as it never occurred. "Data Is a Liability" - Rick Prelinger(posted 10/28/2010) THATCamp finally came to the San Francisco Bay area a couple of weekends ago, and I was fortunate enough to spend an intense 30-hour period thinking and talking about the meteorically trendy digital humanities. As you might imagine, archives were a recurrent conversational topic, and there was tremendous interest in leveraging archival holdings to enable new scholarship, build new applications, and add historical data and sociocultural context to the physical world. There were also provocative moments. My big takeaway turned out to be a throwaway, a comment tossed off during a discussion about, guess what, metadata and the importance of describing raw information. An attendee who had previously worked at an unsuccessful geospatial data company explained what happened when the company closed down and its workers rushed to find new homes for its assets, which were mostly datasets. This, he told us, was difficult, and it was harder because of the need to describe the contents and organization of the data. "Data," he said, "is a liability." Once or twice a year I hear something that ignites my cerebral Roman candles, and that's not necessarily because I'm hearing something I don't want to hear. Actually, his assertion sounded right on the money. If you believe that I truly self-identify as an archivist, that might seem a bit contradictory. Together with Megan, my partner in the library and archives, I collect a lot of data. We collect print materials; we still collect smallgauge film; and, increasingly, we collect both born-digital and digitized moving images and the associated metadata. Is collecting like a game of Hearts, where every gain is also a loss? "Data is a liability." Most of us (especially those in the commercial sector) would describe data as an asset. But let's think historically. Does the value of data ‹ and, by extension, the value of moving images, which are, after all, very rich data ‹ fluctuate over time? And if moving images can be equated to data, might we also say that moving images could become a liability? Before I lose you, let's take a moment to review what this afternoon's version of Wikipedia has to say about fair market value. "Fair market value (FMV) is an estimate of the market value of a property, based on what a knowledgeable, willing, and unpressured buyer would probably pay to a knowledgeable, willing, and unpressured seller.... An estimate of fair market value may be founded either on precedent or extrapolation." OK, let's extrapolate a bit. What's happening with older media, like film and videotape? Microeconomics first: with a few conspicuous exceptions, the price of 16mm and 35mm film on the collectors' market is dropping. While collectors seem to be willing to pay high prices for a few categories ‹ 35mm IB Tech prints of MGM musicals and home movies showing 1930s Europe, to pick a couple of examples ‹ I see a slackening of the frenzy that once characterized eBay. In addition, collectors and independent archivists seeking to sell their holdings to other collectors or to larger archives are running into greater resistance. Why collect film when you can collect DVDs or stream tens of thousands of films from the cloud? Fewer individuals seem to care about preserving their particular versions of the live theatrical experience. On a more macro level, the large archives are filling up. While there are exceptions, there is less and less money and room for large film acquisitions. Staffing is down and storage and processing budgets are static or reduced. While almost no one would dispute the "artistic, cultural and historical" value of moving image collections, their fair market value (such as it is) seems to be decreasing. Several large significant collections languished on the market for a long time before fortunately being acquired by large institutions, and there are still important collections that are hurting for homes. My sense is that this situation prevails in the audio and textual realms as well. Film is becoming a liability, even as the images it contains become more sought after by more people. Fair market value is out of sync with cultural and historical value. Most of us now accept that archives are very likely to digitize most of the videotape they now hold or will accession in the future. As Jim Lindner and Jim Wheeler have often said, the argument that retaining tape backs up vulnerable bits fades as it becomes easier and cheaper to keep multiple disk copies and harder and more expensive to keep tape decks alive. Tape too will become a liability. I would predict that this is likely to happen with film as well, and I'm willing to go out on a limb and say that increasingly high-quality digitization (which equates to oversampling) will cause the sanctions against discarding original film to begin to disappear. What might go first? 16mm release prints for which preprint is known to exist (and later, those not backed by preprint elements); quite possibly network newsfilm collections and very likely some local television news collections. First they came for the newspapers, then they came for the books, now for the films and tapes. (One day, of course, they'll come for the data.) Tape is a liability. Film is a liability. These are incendiary statements. It might be more precise to say that "aging data is a liability," or that "old media is a liability." But just as a society should judge itself by how well it takes care of its most vulnerable members, we might similarly dedicate ourselves as archivists to collecting, preserving and providing access to moving images fixed in dead or dying media. We are in the same position as librarians who guarded in vain hundreds of millions of volumes like Congressional Record, 1920s-era romance novels and old telephone books, except that our managers have mostly not yet ordered us to dispose of physical materials. While I don't want to join the chorus of archivists (and journalists) who reflexively bemoan the loss of tangible assets, there's a real question here. It may well be that we should thin our film and tape holdings, and that digitization/deaccession may be appropriate or unavoidable in some cases. But that's a question for broad discussion. In the past, I've suggested that we take a leaf from the environmental movement and require "digitization impact statements" and "preservation impact statements" when we undertake grand projects, in order to better understand their broad cultural and historical impact. In any case, I don't think that decisions to migrate and destroy material should be made in private. While a single decision may seem trivial or obvious, the sum of many decisions will change history. An aesthete would readily remark that fair market value is the enemy of culture. For archivists, fair market value may be the enemy of the historical record. We would do well to try to reformulate what kind of value matters for us and for the records we try to preserve, and what kind of sense of value we wish to inculcate in our public. Otherwise, the new will continue to discredit the old, and the archival mission will present to the public as an increasingly quixotic pursuit. |

||

The UCLA-produced text and multimedia materials appearing on this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Participant content remains the sole work of the authors. Contact presenters directly for any questions regarding re-use. |